Modern cytometry research, especially in the field of immunology, deals with projects that keep increasing in complexity; often scientists collaborate across multiple institutions, acquire many samples per experiment, and follow many patients over time. This increasing complexity comes with the challenges of managing and integrating results from multiple patients, multiple timepoints, multiple sites and multiple populations of interest.

When approaching the planning of such a “big” research study, one of the most important aspects to consider before starting your research is the amount of data your analyses will generate and how you will manage it. To achieve meaningful results in this type of research, it is key to ensure rigor and reproducibility in the methods you use, meaning not only the technology you use to obtain your results, but also the operating procedure you follow during your experiment.

Indeed, the ability to store, backup and organize your data efficiently can be just as important as your actual results. For instance, following a patient over a long period means you need to compare samples that have been acquired months or even years apart. To successfully complete a study, without missing important findings or losing data, you need to be well organized and able to integrate all the information you have on a single sample. Having a good standard operating procedure in place on how to identify, store and backup your data is fundamental to generate meaningful results. Large and complex projects involving many individuals and timepoints are usually conducted by a team of scientists, each with their own way of organizing data. Even naming the files can become challenging: in a simple flow cytometry experiment counting 3 different panels per patient acquired at 4 different timepoints, you can end up with 12 fcs files per individual, that you need to be able to quickly identify (When was it acquired? Which patient? Which panel?). Storing all this information in the file name can become confusing and when this is multiplied by the number of patients normally present in such a longitudinal experimental setting, the hurdles will become obvious.

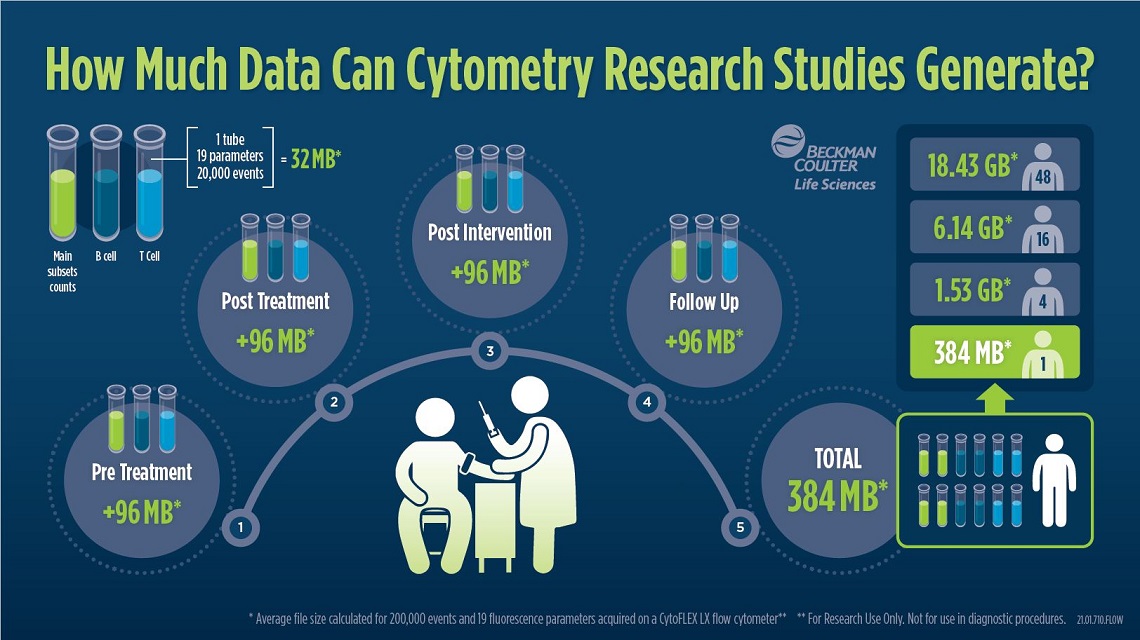

As new technologies enable acquisition of an ever-increasing number of parameters in a single tube, the size of the files you will end up with is an important factor to consider. And until now, we have not even considered experimental controls, panel controls (e.g., Fluorescence Minus One- FMO) or re-run of your test due to error in stainings or flowrate or any other variable you might not be able to control.

Figure 1: The illustration shows an example of the total number of files that could be generated in a simple study and the relative size of the fcs files generated. If 3 tubes of 19 parameters each are collected for each patient at the four most important time points: pre- and post- treatment, post-intervention and follow up. The FCS files of a patient alone have a size of about 384 MB with the given parameters. Added to this are metadata such as patients ID, experiment number or outcome/biomarker. Download Infographic

Also, to be even more efficient, you will need to find a good solution where to store, along with all the files, other information related to that experiment, such as staining protocols or any other metadata connected to those samples, so that you will be able at anytime to recall every variable of the experiment. Finding a way to link final results to raw data will save you so much time when edits will be requested.

Organizing files is critical in studies. Keeping all generated files clear and organized requires well designed work instructions across all involved laboratories. Thinking about data first is key to success.